This is an article from The Guardian by

George Monbiot. In this project i will be creating 3 images to accompany this article. The 3 images will fit set dimensions and and be limited to 2 colours plus the stock/paper. The images will be used to communicate the idea central to the text. Each of the 3 images must be distinct but work as a set/series that are visually consistent. I need to avoid generalisations and vague messages.

Things i need to consider-

- What tone of voice will i adopt?

- How will i create a functional image, visual metaphors?signs? symbols?

- How to illustrate the relationship between character and object?

"What do we call this time? It’s not the information age: the collapse

of popular education movements left a void filled by marketing and

conspiracy theories.

Like the stone age, iron age and space age, the digital age says plenty

about our artefacts but little about society. The anthropocene, in

which humans exert a major impact on the biosphere, fails to distinguish

this century from the previous 20. What clear social change marks out

our time from those that precede it? To me it’s obvious. This is the Age

of Loneliness.

When Thomas Hobbes claimed that in the state of nature, before authority arose to keep us in check, we were engaged in a war “

of every man against every man”,

he could not have been more wrong. We were social creatures from the

start, mammalian bees, who depended entirely on each other. The hominins

of east Africa could not have survived one night alone. We are shaped,

to a greater extent than almost any other species, by contact with

others. The age we are entering, in which we exist apart, is unlike any

that has gone before.

Three months ago we read that loneliness has become an

epidemic among young adults.

Now we learn that it is just as great an affliction of older people. A

study by Independent Age shows that severe loneliness in England blights

the lives of

700,000 men and 1.1m women over 50, and is rising with astonishing speed.

Ebola is unlikely ever to kill as many people as this disease strikes

down. Social isolation is as potent a cause of early death

as smoking 15 cigarettes a day; loneliness, research suggests, is

twice as deadly as obesity. Dementia, high blood pressure, alcoholism and accidents – all these, like depression, paranoia, anxiety and suicide, become

more prevalent when connections are cut. We cannot cope alone.

Yes, factories have closed, people travel by car instead of buses,

use YouTube rather than the cinema. But these shifts alone fail to

explain the speed of our social collapse. These structural changes have

been accompanied by a life-denying ideology, which enforces and

celebrates our social isolation. The war of every man against every man –

competition and individualism, in other words – is the religion of our

time, justified by a mythology of lone rangers, sole traders,

self-starters, self-made men and women, going it alone. For the most

social of creatures, who cannot prosper without love, there is no such

thing as society, only heroic individualism. What counts is to win. The

rest is collateral damage.

British

children no longer aspire to be train drivers or nurses – more than a

fifth say they “just want to be rich”: wealth and fame are the

sole ambitions of 40% of those surveyed. A government study in June revealed that

Britain is the loneliness capital of Europe.

We are less likely than other Europeans to have close friends or to

know our neighbours. Who can be surprised, when everywhere we are urged

to fight like stray dogs over a dustbin?

We have changed our language to reflect this shift. Our most cutting

insult is loser. We no longer talk about people. Now we call them

individuals. So pervasive has this alienating, atomising term become

that even the charities fighting loneliness use it to describe the

bipedal entities formerly known as human beings.

We can scarcely complete a sentence without getting personal.

Personally speaking (to distinguish myself from a ventriloquist’s

dummy), I prefer personal friends to the impersonal variety and personal

belongings to the kind that don’t belong to me. Though that’s just my

personal preference, otherwise known as my preference.

One of the tragic outcomes of loneliness is that people turn to their

televisions for consolation: two-fifths of older people report that

the one-eyed god is their principal company. This self-medication aggravates the disease. Research by economists at the University of Milan suggests that

television helps to drive competitive aspiration.

It strongly reinforces the income-happiness paradox: the fact that, as

national incomes rise, happiness does not rise with them.

Aspiration, which increases with income, ensures that the point of

arrival, of sustained satisfaction, retreats before us. The researchers

found that those who watch a lot of TV derive less satisfaction from a

given level of income than those who watch only a little. TV speeds up

the hedonic treadmill, forcing us to strive even harder to sustain the

same level of satisfaction. You have only to think of the wall-to-wall

auctions on daytime TV, Dragon’s Den, the Apprentice and the myriad

forms of career-making competition the medium celebrates, the

generalised obsession with fame and wealth, the pervasive sense, in

watching it, that life is somewhere other than where you are, to see why

this might be.

So

what’s the point? What do we gain from this war of all against all?

Competition drives growth, but growth no longer makes us wealthier.

Figures published this week show that, while the income of company

directors has risen by more than a fifth, wages for the workforce as a

whole have fallen in real terms over the past year. The bosses earn –

sorry, I mean take – 120 times more than the average full-time worker.

(In 2000, it was 47 times). And even if competition did make us richer,

it would make us no happier, as the satisfaction derived from a rise in

income would be undermined by the aspirational impacts of competition.

The top 1% own 48% of global wealth, but even they aren’t happy.

A survey by Boston College

of people with an average net worth of $78m found that they too were

assailed by anxiety, dissatisfaction and loneliness. Many of them

reported feeling financially insecure: to reach safe ground, they

believed, they would need, on average, about 25% more money. (And if

they got it? They’d doubtless need another 25%). One respondent said he

wouldn’t get there until he had $1bn in the bank.

For this, we have ripped the natural world apart, degraded our

conditions of life, surrendered our freedoms and prospects of

contentment to a compulsive, atomising, joyless hedonism, in which,

having consumed all else, we start to prey upon ourselves. For this, we

have destroyed the essence of humanity: our connectedness.

Yes, there are palliatives, clever and delightful schemes like Men in

Sheds and Walking Football developed by charities for isolated older

people. But if we are to break this cycle and come together once more,

we must confront the world-eating, flesh-eating system into which we

have been forced.

Hobbes’s pre-social condition was a myth. But we are entering a

post-social condition our ancestors would have believed impossible. Our

lives are becoming nasty, brutish and long."

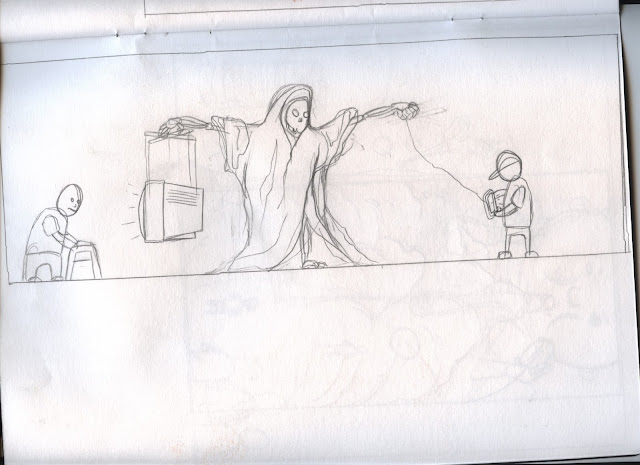

This image shows death drawing in 2 different generations using different forms of technology. I wanted to show how advances in technology have changed the way digital media affects people in terms of causing or being a symptom of loneliness.

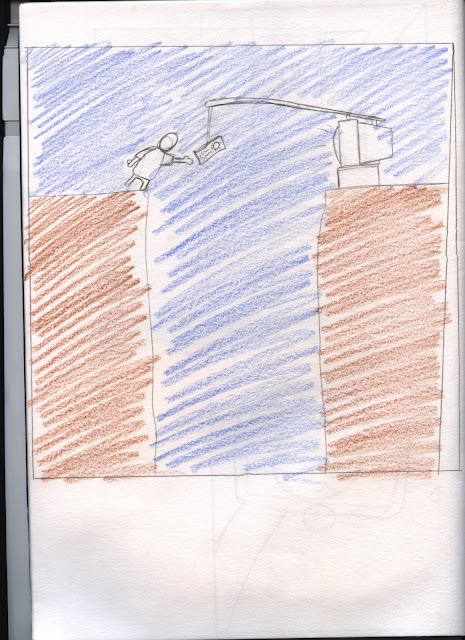

With this image i wanted to show the way that television promotes unobtainable levels of wealth and celebrity that mean people will never be happy with their lives no matter how successful they become.

The idea behind this design id to show the health implications of loneliness. I tried to keep the image simple and bold and use colours that would the message.

This image is designed to show the way that a competitive society drives people to view each other as competition and that we should set our own goals instead to looking at others accomplishments.

This picture shows a mobile phone as the pied piper leading the youth of today away from themselves and each other.

I got the idea for this picture from Scrooge McDuck. I wanted to show how even the most well off people in the world feel they need an average of 25% more than they have now to be financially safe. At which point they will most likely decide they need an extra 25% again.

In this image i tried to show how mobile phones allow people to see the entire world while sat in their own home, something that has caused people to spend more time alone at home.

For this illustration I have drawn the central character in a hospital bed thinking about the things that have had negative affects on their health. The thought bubbles illustrate loneliness and the quest for wealth.